Black Power in Print

Emory Douglas, The Black Panther newspaper, vol. 4, no. 5 (“Selected Works of the Black Panther Party”) (detail), 1970. Published by the Black Panther Party. Two-color ink on newsprint. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Collection of Patrick and Nesta McQuaid and Akili Tommasino, gift of the Committee on Architecture and Design Funds. © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Emory Douglas, The Black Panther newspaper, vol. 4, no. 5 (“Selected Works of the Black Panther Party”) (detail), 1970. Published by the Black Panther Party. Two-color ink on newsprint. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Collection of Patrick and Nesta McQuaid and Akili Tommasino, gift of the Committee on Architecture and Design Funds. © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In April 2021, MFA staff recovered a document long overlooked in the Museum’s archives: “A Proposal to Eradicate Institutional Racism at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.” Written in 1970 by Boston-based artist, muralist, and community organizer Dana C. Chandler Jr. (b. 1941), the manifesto challenges the MFA (and, by inference, similar institutions) to represent Black artists in their collections and exhibitions, and to financially support Black self-determination in the arts.

Chandler’s rallying cry helped push the MFA to stage the exhibition “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston” in spring 1970. One of 70 artists featured, Chandler showed a portrait of Black Panther Party national chairman Bobby Seale as well as a painting that marked the recent murder of the young Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton. In 2020—50 years after that exhibition—the MFA acquired Fred Hampton’s Door 2, the second and only surviving version of Chandler’s seminal painting, for its permanent collection. Similarly, in 2019, the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired an archive of The Black Panther newspaper, published between 1967 and 1980. Designed and illustrated by Emory Douglas (b. 1943), the Black Panther Party’s minister of culture, the newspaper defined the party’s signature visual identity, while its pages chronicled the same national and international struggles examined in Chandler’s manifesto and art.

This online project—a collaboration between the MFA and MoMA—acknowledges the belated institutional recognition of these foundational documents and artworks as part of a broader examination of the Black Power movement’s legacy in visual culture. The recent digitization of Chandler’s manifesto and issues of The Black Panther newspaper offer unprecedented access to archival materials, and new interviews between artists and scholars provide trenchant historical analysis. This archive of documents and conversations will continue to grow, connecting past and present struggles, informing a contemporary politics of resistance, and illustrating how print media of many kinds remains a key means of agitation against racial inequity and in support of the Movement for Black Lives.

Continue exploring the visual legacy of the Black Power movement through MoMA’s “Emory Douglas: Art and Revolution” project.

Image Gallery

In the late 1960s and ’70s, the Black Power movement utilized graphic imagery to promote its political platform and communicate Black experience to broad communities. These images tell fragments of that story.

Published by the Black Panther Party. Two-color ink on newsprint. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Collection of Patrick and Nesta McQuaid and Akili Tommasino, gift of the Committee on Architecture and Design Funds. © Emory Douglas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Emory Douglas, The Black Panther newspaper, vol. 4, no. 5 (“Selected Works of the Black Panther Party”), 1970

A four-page newsletter at its inception in Oakland, California, in 1967, The Black Panther was the official newspaper of the Black Panther Party. Founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, it was distributed in cities across the United States as well as internationally.

Published by the Black Panther Party. Two-color ink on newsprint. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Collection of Patrick and Nesta McQuaid and Akili Tommasino, gift of the Committee on Architecture and Design Funds. © Emory Douglas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Emory Douglas, The Black Panther newspaper, vol. 3. no. 13 (“Avaricious Businessman”), 1969

Graphic artist Emory Douglas created the The Black Panther newspaper’s visual protest vocabulary, often using cut-and-paste collage techniques and prefabricated type from Formatt (a Letraset alternative).

Published by the Black Panther Party. Two-color ink on newsprint. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Collection of Patrick and Nesta McQuaid and Akili Tommasino, gift of the Committee on Architecture and Design Funds. © Emory Douglas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Emory Douglas, The Black Panther newspaper, vol. 4. no. 2 (“Fred Hampton Murdered”), 1969

“Initially, wherever we were set up, [usually in someone’s home], that would be our production area. We used regular tables, regular lights, Elmer’s glue, rubber cement. We cut and pasted. We made up our own layout sheets. Non-repro blue markers. A lot of it was done on [an IBM Selectric] typewriter.” —Emory Douglas

Published by the Black Panther Party. Two-color ink on newsprint. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Collection of Patrick and Nesta McQuaid and Akili Tommasino, gift of the Committee on Architecture and Design Funds. © Emory Douglas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Emory Douglas, The Black Panther newspaper, vol. 4. no. 2 (“Fred Hampton Murdered”), 1969

This spread documents the police murder of Chicago-based Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, an act of violence that Dana Chandler would later commemorate in his work.

Acrylic paint on wood. William Francis Warden Fund, The Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection, and Gallery Instructor 50th Anniversary Fund. © Dana C. Chandler Jr.

Dana C. Chandler Jr., Fred Hampton’s Door 2, 1974

Dana Chandler created Fred Hampton’s Door 2 following the theft of his small painting Fred Hampton’s Door (1970), which he made in response to the violent murder of the young Black Panther Party leader. Both works commemorate Hampton while protesting and mourning the violent circumstances of his death. Chandler used an actual door for the second version to ensure it could not be as easily stolen. Though the original painting was exhibited at the MFA in 1970, it was not until 50 years later, in December 2020, that this major work by Chandler finally entered the Museum’s collection.

Lithograph. Gift of Impressions Workshop. © Dana C. Chandler Jr.

Dana C. Chandler Jr., Black People break free of the Sucking, Mother-F—ing White Egg, from the portfolio Fifteen Days in May, 1968

Chandler released Black People break free of the Sucking, Mother-F—ing White Egg as part of a portfolio published by the Impressions Workshop in 1968 in collaboration with Artists Against Racism and the War (AARW). It was dedicated to the memory and ideals of Martin Luther King Jr. in the wake of his assassination. According to curator and scholar Makeda Best, “The portfolio formed a major component of Fifteen Days in May, the AARW’s wide-ranging program of murals, poetry readings, exhibitions, and performances.” (From Art in Print, March/April 2014). This modestly sized numbered print was the only work by Chandler in the MFA’s collection until late 2020.

All artwork pictured © Dana Chandler Jr.

Dana Chandler with Fred Hampton’s Door and other artwork, Roxbury, MA, 1973

In early 1970, Chandler channeled his rage over the murder of yet another gifted and charismatic young Black leader by creating the first version of Fred Hampton’s Door. According to Time magazine, the work was permeated with actual bullet holes. In Chandler’s words: “I remember spending a great deal of time...being very publicly angry about the killing of this brilliant young man just because what he was trying to do was get both Blacks and whites together in a movement to make things better for people of color and poor people. He was a young version of Martin Luther King and they killed him outright.”

© Dana C. Chandler Jr.

Dana C. Chandler Jr., study of Fred Hampton’s Door, about 1973

When making the original version of Fred Hampton’s Door, Chandler recalled: “I wasn’t just thinking about [Fred Hampton]. I was thinking about how many Black people were dying because the police has gone berserk as they had all over the country.... I was thinking about all of that, how it was nonstop all the time, every single goddamned day, and I was so pissed. That’s how that came about, and it hasn’t ceased.”

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Archives.

Dana Chandler, “A Proposal to Eradicate Institutional Racism at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts,” 1970

In 1970, Chandler wrote “A Proposal to Eradicate Institutional Racism at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts,” a manifesto challenging the MFA (and, by inference, similar institutions) to represent Black artists in their collections and exhibitions, and to support Black self-determination in the arts by financially backing Black-centered arts institutions. The manifesto and subsequent exchange between Chandler and then MFA director Perry T. Rathbone is available online as part of “Black Power in Print.”

Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists records (M042). Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts. Box 26, Folder 3.

Artist Bill Rivers gives a gallery talk in “Afro‐American Artists: New York and Boston,” 1970

Shortly after Chandler wrote his manifesto, the MFA formed a partnership with the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists (NCAAA). Together with the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, the institutions collaborated on the exhibition “Afro‐American Artists: New York and Boston.” On view from May 19 to June 23, 1970, the exhibition was part of larger conversations around equity of representation in cultural organizations at the time.

Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists records (M042). Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts. Box 26, Folder 3.

Edmund Barry Gaither gives a gallery talk in “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston,” 1970

“Afro American Artists” was curated by Edmund Barry Gaither, then the newly appointed director and curator of the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists and a special consultant to the MFA.

Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists records (M042). Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts. Box 26, Folder 1.

Promotional poster for “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston,” 1970

Illustrator Jerry Pinkney and designer Tom McCarthy designed the “Afro-American Artists” catalogue and marketing materials, which featured a photograph by artist Robert Boardman Howard.

Photograph by Spencer Grant.

Boston’s Post Office Square protest, 1970

On May 1, 1970, activists gathered in Boston’s Post Office Square to protest the trial of Black Panther national chairman Bobby Seale. The crowd was met with speeches by area captain Doug Miranda and Seale’s then wife Artie Seale. Around the same time, Dana Chandler created a large-scale portrait of Bobby Seale, which he would soon show in “Afro-American Artists.”

Published by the Black Panther Party.

The Black Panther newspaper, vol. 5, No. 2 (“What We Want What We Believe. Black Panther Party Platform and Program”), 1969

The Black Panther Party, originally known as the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, created a platform in October 1966 in response to police violence, discrimination, and inequity. This document was published in every issue of The Black Panther newspaper from 1967 until 1980, when the paper went out of circulation. Chandler read the newspaper and attended party meetings in Boston around the time he crafted and delivered his own manifesto, list of demands, and plan of action to the MFA.

Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists records (M042). Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts. Box 26, Folder 3. All artwork pictured © Dana C. Chandler Jr.

Dana Chandler gives a gallery talk in “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston,” 1970

Dana Chandler gives a gallery talk on his portrait of Bobby Seale, the national chairman of the Black Panther Party who was on trial in New Haven, Connecticut, at the time. Under Chandler’s arm is the small head of his then six-year-old daughter, Dahna. In 2021 she recalled that the MFA “did not feel like a space that was welcoming. To be honest, most spaces that were white dominated did not feel like welcoming spaces to me, and the Museum of Fine Arts at the time was not an exception to that rule.”

Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists records (M042). Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts. Box 26, Folder 3. All artwork pictured © Dana C. Chandler Jr.

Dana Chandler gives a gallery talk in “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston,” 1970

Following much controversy leading up to “Afro-American Artists” opening, Chandler wrote, “This is a very, very major show.... Its significance to me as a Black man, a Black parent, and a member of a dynamic Black community (as well as one of several catalysts for this exhibit) becomes obvious when one remembers that this will be the first time that my children, my parents, and my community will see a major show about them and of them sponsored by a Black institution in a major white institution. This is both a joy and a tragedy. A joy because of what my children and the children of my community will at last see; a tragedy that it happened so long after my parents’ childhood. However, the joy immeasurably transcends the tragedy.” (From “Notes from a Black Artist,” May 1970. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Archives.)

Annotated Bibliography

Explore further reading inspired by a list from Chandler’s 1970 manifesto.

Acknowledgements

Every museum project takes many heads and hands to put together, and “Black Power in Print” is no different. The MFA acknowledges the following people:

Curatorial team: Michelle Millar Fisher, Ronald C. and Anita L. Wornick Curator of Contemporary Decorative Arts; Liz Munsell, Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art; Reto Thüring, Beal Family Chair, Department of Contemporary Art; and Akili Tommasino, former associate curator of modern and contemporary art.

Creative Services, Intellectual Property, and Archives staff: Jill Bendonis, Katherine Campbell, Megan Conway, Sarah Kirshner, Maggie Loh, Jane Martin, Maureen Melton, Janet O’Donoghue, Matthew Whiman, and James Zhen.

We offer sincere thanks to our esteemed external project contributors: Chenoa Baker, Dana C. Chandler Jr., Dahna Chandler, Bouchra Khalili, Kelli Morgan, and Jackie Wang.

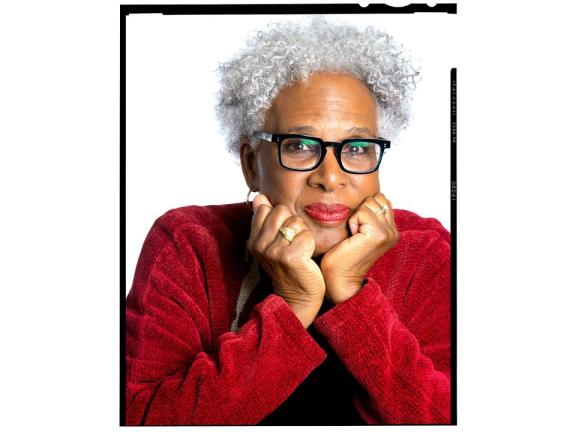

And our esteemed program participants: Margaret Burnham, Dana C. Chandler Jr., Doug Miranda, and Nell Painter.

We acknowledge with gratitude colleagues at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, with whom we had many generative conversations throughout this project. They kindly allowed us to use images from their holdings of The Black Panther newspaper, which our former colleague Akili Tommasino brought into their collection in 2019—the act that precipitated our project.

This project would not have been possible without the generosity and skill of archivist Molly Brown from the Northeastern University Library’s Archives and Special Collections, and the assistance of Molly Copeland.